Another study published showing how rearing monarchs on tropical milkweed doesn't help them

- Andy Davis

- Oct 6, 2020

- 7 min read

Updated: Mar 22, 2022

Hello everyone,

As you can see from this blog title, a brand new study was just published, and it is definitely one that everyone needs to hear about. I just read it myself and I'll do my best to describe it here.

I know what you're thinking - here we go again with the tropical milkweed thing. This is indeed a touchy subject for some folks out there, who really, really love the tropical milkweed in their gardens, and they don't want any scientists telling them not to use it. This subject, and the controversy over it, has been brought up many times before, and it's always the same story - a new study comes out that provides evidence that this non-native plant is bad for monarchs, often with a big press release, and then the story makes the rounds on social media, getting people worked up, and then everyone on social media tries to argue for why the study was 1) flawed or 2) does not pertain to them. These social media arguments can sometimes get out of hand, and for some reason, these arguments sometimes lead people to believe this issue is not yet settled, or that there is support for "both sides" of the tropical milkweed issue, which isn't true at all.

Well folks, you can feel free to argue all you want about this new study. After reading it, I can see that it definitely has some limiting issues, but then again, it also contains some brand new results that I've never seen before. Either way, if you at all care about monarchs, then you should at least be aware of this new study, even if you simply want to find a way to poke holes in it.

The paper in question is titled, "Effects of diet and temperature on monarch butterfly wing

morphology and fight ability", and it was published in the Journal of Insect Conservation. Here is a link. The paper was co-authored by Abrianna J. Soule, Leslie E. Decker & Mark D. Hunter. I don't know the first two people, but I do know that Mark is a world expert on milkweed and the effects of their toxic cardenolides.

As the title of the paper indicates, the goal of this study was to determine how different milkweeds affect how well monarch caterpillars grow into functioning adults, and also to determine if temperature affects this growth.

For the monarchs, one of the most important and challenging times in their lives is their fall migration. This is an extremely risky and strenuous journey that requires absolute perfection in their migratory capability. From a research perspective, determining how capable a monarch is of successful migration can be done essentially by examining their wings - how big they are and how they are shaped, and this is what these researchers did. A boatload of prior research has now shown how monarchs need to have very large, and very elongated wings for optimal migration. Those that do not have these will tend to be weeded out of the migration (that means they'll die trying). This is a classic case of natural selection. And, since this has been happening over hundreds, if not thousands of years, this is why eastern North American monarchs have large, elongated wings, and all other populations, well, don't.

For their experiment, they had over 200 monarch larvae that were the progeny of monarchs collected from the wild and also purchased from MonarchWatch. They reared the larvae on three different milkweeds - Ascepias incarnata (swamp milkweed), Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed) and Asclepias curassavica (tropical milkweed). Each of these differs in the concentration of cardenolides (the milkweed toxin) - tropical has a lot, while swamp has the least, and common is in the middle. These differences allowed the researchers to determine how variation in cardenolides at the larval stage affects growth of the wings.

They also reared their larvae in one of two temperatures - 25C and 28C (or 77F and 82F). I should have pointed out earlier that the rationale for examining this temperature effect is fairly obvious - to see how the future warming of the planet will affect the monarch.

I'm not going to get into the details of the rearing, since other than the temperatures and the different milkweeds, it seemed pretty straightforward, except for one issue that I'll discuss later. Once all of the larvae were reared to the adult stage, they performed a series of measurements on them, and also tested their flight ability. First, they measured the size and shape of their wings. Here, they used image analysis techniques, which is where you scan the butterfly on a flatbed scanner, and then use computer software to compute whatever measurements you need on the wing images. Below is a figure from the paper, which shows this measurement. You can see that one of the most important measurements is the aspect ratio of the forewing (pictured on the far right), which is a ratio of the length divided by the width. If this ratio is large, then the wing is elongated, and if it is small, then the wing is more rounded. Remember, being elongated is better for optimal migration.

The researchers actually performed a number of additional, very sophisticated measurements of the wing shape, but in the end, I'm not sure if they were needed, since the wing elongation appeared to be the most important result - see below.

After they had measured the wing features, they used a flight mill apparatus to assess the flight ability of the monarchs in each milkweed and temperature group. I've talked about these things before - this is a tabletop device with a rotating rod that spins in a circle. The monarch is attached to the rod, and flies around and around, while a computer tracks its speed and distance. In addition to measuring how far the monarchs flew, they also measured how much mass the monarchs lost while flying. This is a nifty way to assess how much energy the monarchs had to use to make these flights - a migrating monarch needs to use as little energy as possible.

Finally, as a check of their rearing procedures, the researchers measured cardenolide content of the adult monarchs to confirm their dietary treatments - they found that monarchs that grew up eating tropical milkweed had the highest levels of cardenolides, while those that ate swamp milkweed had the lowest.

Here is what they found:

Temperature had a very clear effect on monarch flight - regardless of which milkweed they were reared on, monarchs reared under higher temperatures did not fly as far on the flight mill, and they lost more mass during flight than those reared under control temperatures. This result has some pretty obvious implications for a future, warmer world. As temperatures continue to rise, monarchs will be less capable of flight.

Their analyses of the different milkweed effects on flight showed that this effect was not as strong as the temperature effect, although there was an effect. In the paper, there is a lot of discussion and text devoted to how this effect was manifested, but I think a simple visual here would suffice. I noted that this was lacking in the paper itself, so I made one!

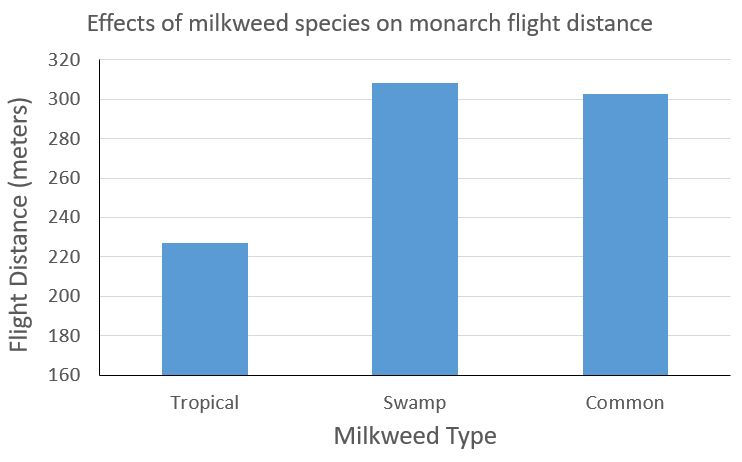

The researchers provided their complete data from their experiments as a downloadable Excel file along with the publication. From this file, I made my own graph showing how different milkweed species affect adult flight. For this, I use their data to compute the average distance flown (in meters) for all monarchs that were reared on tropical vs swamp vs common milkweed. Below is what I found:

This graph shows that the monarchs reared on tropical milkweed did not fly as far as those in the other groups. Keep in mind though that this effect was not as statistically significant as the temperature effect.

OK, for the wing measurements, the biggest result was that those monarchs reared on tropical milkweed had the least elongated wings. This was a highly-significant effect, and one that the researchers highlighted in the paper and in the abstract. Recall that for migrants, their wings need to be as elongated as possible. Because of this, the researchers concluded that tropical milkweed produces monarchs that are less-suited for migration as those reared on other milkweeds.

Below is a figure taken from the paper that shows the wing aspect ratio (elongation) results.

One of the other really neat ancillary findings from this project was in their flight mill data. They reported that the monarchs with the most elongated wings did not lose as much mass during flight as did those with less elongated wings. This was very very cool - it is the first empirical demonstration of this idea that wing elongation is important for optimal migration. And, it shows how monarchs produced on tropical milkweed would have a much harder time reaching Mexico, because their wings are simply not as "optimally-designed".

OK, there was one glaring problem with this study that I saw, but to be fair, the authors did a commendable job at trying to fix it. The authors reported that even though they maintained a clean rearing operation and even bleached their milkweed, they ended up having a very high level of OE infections in their adult monarchs. They did not report exactly how high in the paper, but from their data provided in the supplemental material, you can figure it out. I did, and it looks like about 90% of the monarchs in the experiment were infected! Whoah. This is a really bad outbreak, and it makes me wonder if their rearing operation really was as clean as they stated.

As I said, this is a big problem. It means that most of the data and results from their experiment only pertain to infected monarchs. The question then is, can these findings be applied to healthy monarchs? Well, yes and no. I see that the researchers at least tried to statistically account for the infections in their analyses, by incorporating an infection level predictor in the tests. This is like asking the statistical test to "factor in" the level of infection, and then to remove it from the test thereafter. To me, this is sort of like making lemonade from lemons.

So from my read, this paper had some strengths and weaknesses, but for sure, it presents some new findings.

As a summary, here is my take-away points from this paper:

- increasing temperatures during monarch development appear to negatively affect adult monarch flight potential

- caterpillars that develop on tropical milkweed grow into adults with wings that are not optimal for migration

As a final point, before you go and share this post on your favorite monarch Facebook group, please don't buy into the idea that this research on tropical milkweed is not yet settled. It very much is. No reputable monarch scientist recommends that people plant or use tropical milkweed in their gardens or in their homes for rearing. I know this because I surveyed them.

Kudos to the authors for this very, very interesting new paper!

That's all for now.

Cheers

**********************************************************************************************

Direct link to this blog entry:

**********************************************************************************************